With all the students on summer break now, the campus is empty – just the way I like it for my daily stroll.

Two of my favorite landmarks on the college campuses.

Sandy and I rarely eat out, so this was quite a treat for us to have breakfast al fresco at the Village Grille.

Sandy did a great job steering me in the right direction toward the shoes.

If we’re going to assert that poetry is work, we need to go beyond the semantics and difficulty and consider how it’s valued alongside other types of labor. The movie Paterson and Jim Jarmusch give us the opportunity to compare the work of making poetry with material forms of creative work and the waged work of bus driving. By highlighting the contrast between Paterson writing at work and his wife Laura making things at home, we’re immediately confronted with the historically lopsided and gendered division of labor that takes place in the public and private spheres.

Political philosopher Hannah Arendt argued that the division of public and private realms is partially linked to the prioritization of intellectual over manual labor in classical Greek society. Arendt saw poetry, which is made purely of language, as the most human and least worldly of the arts. On the other hand, Richard Sennett saw craft as a merging of mental and manual labor, with the products representing the intimate connection between the hand and head.

However, the American philosopher Richard Sennett acknowledges that not all crafts are seen as equal, with parenting being viewed as different in character than plumbing or programming. Jarmusch defends the character of Laura against accusations of regressive gender roles, pointing out that she lives how she wants and is entrepreneurial, even if it’s in a domestic set-up. Jarmusch sees domesticity as a fact of how social structure works, but he also emphasizes the essential difference between the approaches to their respective crafts of the two main characters.

“River of Grass” is a film that explores the theme of insignificance in the grand scheme of the universe. Set in the Florida Everglades, the film follows Cozy, a bored housewife, and Lee, a gregarious stranger she meets in a bar.

After a series of events, the pair become convinced that they have killed a man and go on the run. However, their actions feel inconsequential against the backdrop of the vast and unyielding natural world. The film’s ending shot of freeway gridlock heading off into the distance further reinforces this theme. The characters in the film exaggerate their own importance, but Reichardt ultimately suggests that life existed long before they came along and will continue long after their drama has ended.

Director Kelly Reichardt is known for using natural space in her films to convey the idea that the world goes on regardless of human activity. This is evident in “River of Grass” through the use of the Everglades as a setting, as well as the film’s ending shot of freeway gridlock heading off into the distance. The characters in the film exaggerate their own importance. Still, Reichardt’s film ultimately suggests that life existed long before they came along and will continue long after their drama has ended.

While the meandering apathy of “River of Grass” can be a challenge for viewers, Reichardt’s wit and skill as a filmmaker make it worth a watch. The film may be a bit too ethereal for some, but this could very well be the point as it suggests that our individual experiences and struggles are insignificant in the grand scheme of things. If you’re a fan of Reichardt’s later work or enjoy films that ponder the larger questions of existence, “River of Grass” is definitely worth checking out.

I’m proud of this 8mm home movie I filmed last summer around the colleges in Claremont, California. Some of the landmarks I filmed ended up in the movie I shot this winter called Winter Dreams, which is now in post-production.

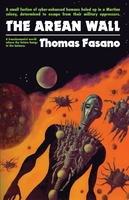

I produced the documentary film BIGFOOT TIM. The film recounts the last ten years of his deceased twin brother’s life, using over 1,500 of Tim Fasano’s YouTube videos plus archival content such as 8mm home movies, newspaper articles, podcast segments, and recorded radio interviews.

I made the film with a total budget of $79, using the Filmora software on an older iMac.

A little background: Tim was born in Virginia and eventually settled in the Tampa area. The film explores the last decade of his life as he struggles to pull himself out of poverty as a cab driver while developing a late-life interest in videography and a passion for finding Bigfoot in the swamps of Florida. The film brims with wild stories, wild characters, strange dreamers, and big ideas about human existence.

The soundtrack uses 31 compositions by the Australian/Swedish composer Scott Buckley. It also uses the song “Wishes” by American guitarist, singer, and songwriter Matthew Mondanile, performed by his solo music project, Ducktails.

Robert Caro shows off his typewriter and also gives a succient explanation of his writing process and how to avoid “thinking with your fingers.” Watch as Caro himself explores some of the key objects in the exhibition. In this episode, he describes one of his trusty Smith Corona Electra 210 typewriters, a brand that he’s worked on for decades and that has become an essential part of his writing process.

New-York Historical’s exhibition “Turn Every Page”: Inside the Robert A. Caro Archive showcases never-before-seen highlights from life and career of Robert Caro, the Pulitzer Prize-winning author behind such masterful biographies as The Power Broker and the multi-volume series The Years of Lyndon Johnson.

A trailer I did for the documentary about my twin brother and his exploits searching for Bigfoot. It took a lot of work to put this short film together, but it was fun.

For the most part, the well-known facts about Andy Warhol’s life are covered in the first hour of Ryan Murphy’s six-part Netflix documentary The Andy Warhol Diaries. When he was younger, he drew portraits of his classmates in an attempt to stop them from bullying him; he also had a fondness for Campbell’s tomato soup; and he left Pittsburgh in 1949, when he was just 20 years old. After making the switch from graphic design to fine art, he opened The Factory in Union Square, where he exhibited his first soup cans in 1962 and went on to become a pop star by 1968.

Warhol’s inner life is the subject of director Andrew Rossi, who focuses mostly on the artist’s complicated connection with his homosexuality. Using a mix of archival and newly shot material, the documentary tells the story of Warhol’s intense feelings for three key characters: interior designer Jed Johnson, Paramount Pictures vice president Jon Gould, and artist Jean-Michel Basquiat. By all accounts, Warhol’s attraction to Basquiat was parental, sexual, and opportunistic. The primary tone is one of intense loneliness, as a voice like Warhol’s reads sections from his journal, a blend of actor Bill Irwin and a somewhat robotic drone of artificial intelligence.

After leaving Pittsburgh’s oppressive homophobia, he moved to New York City, where other gay artists like Robert Rauschenberg and Jasper Johns radiated a machismo he could not begin to conjure.

Then Rossi turns to Warhol’s relentless cultivation of his own persona. Meticulous yet glamorous—his trademark silver wigs are shown off by Jessica Beck of the Warhol Museum—the artist built a perfectly constructed persona, one that he often used as a defense mechanism. “The way he presented himself was as asexual,” says Fab Five Freddy. “You would hear rumors, but he publicly kept that aspect of his life out of the picture.” In the film, he describes the various young, beautiful, or powerful people whom Warhol regularly surrounded himself with: Keith Haring, Andy Kaufman, Basquiat, and Jon Gould (the subject of his last film). Warhol often hid behind these figures in an attempt to mask his persistent fears of ageing and irrelevance.

Warhol’s diaries, do not remind me of a medieval saints, nor even of a kept mistress, but of the secret lovesick grumblings of servant-boy, frustrated in an attic turret. One therefore assumes that Warhol’s diary is less than a masterpiece of the genre. But this is not the impression conveyed by Mr. Rossi’s film, which insinuates itself into the territory of Proust and Henry James with its wet and spongy footsteps. “I wouldn’t be surprised if they started putting gays in concentration camps,” Warhol writes. It is only what you would expect from such a louche observer, such a tone-deaf man of fashion—those sneakers, those sunglasses!—and such an aesthete, who still, despite his fame and fortune, thought himself a member of some oppressed minority. Much of the language of Warhol’s time is problematic today, including his references to Basquiat as “the big black painter” or Aids as “gay cancer.” You can blame yourself if you remain in doubt about this film’s intentions. Strictly speaking, it has none. It is not trying to understand Warhol or his work, or to interpret either in any way. It is a bath that has been prepared for you; into it you must sink for as long as the water remains warm.